Something that is often ignored in the histories of the First World War is the role that leisure time played in the soldiers' lives. I recently came across the work of Sarah Cozzi and was fascinated to read that she has put a great deal of research into how Canadian troops spent their leaves overseas, and the information for this post comes from her Master's thesis, "Killing Time: The Experiences of Canadian Expeditionary Force Soldiers on Leave in Britain, 1914-1918," and “'When You’re A Long, Long Way From Home:' The Establishment of Canadian-Only Social Clubs for CEF Soldiers in London, 1915-1919," an article for the Canadian War Museum.

To begin, it is important to mention that neither the Canadian government nor the military authorities involved themselves in the soldiers' off-duty time. However, Cozzi asserts that those periods of leisure spent by Canadian soldiers overseas played an important role in shaping their experiences of the First World War.

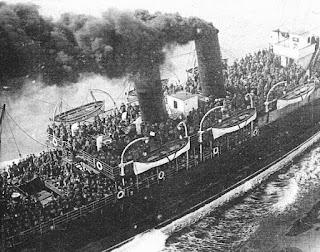

|

| A fully laden troopship leaving Folkestone Harbour for Boulogne |

Cozzi also describes the CEF's system of leave grants: "Recruits were expected to spend the majority of their time in camp, where much of their day was spent learning how to soldier... However, despite the limited off-duty time available, there was still opportunity for soldiers to obtain leave passes, allowing them to travel past the boundaries of their camps and to venture into the surrounding villages. As always, however, men could be recalled to their units at a moment's notice, and had to remain ready should they be requested to do so. Leave passes were much sought-after commodities,and were considered a luxury to which everyone looked forward to with eager anticipation... Upon first arrival in England, soldiers were handed leave passes, with all ranks assigned six days' leave upon disembarkation, allowing them free passage anywhere in the British Isles. But no more than twenty percent of the numbers of a unit were allowed to travel at any one time."

London quickly became the main destination for service personnel, which presented a host of problems generally caused by a large influx of young men with free time and access to alcohol. A number of groups both locally and from back in Canada began to recognize the need for organized and wholesome social gathering places. The Red Cross, YMCA, and Canadian War Contingent Association (CWCA) operated in both England and France, but were predominantly concerned with providing basic necessities and food to the men rather than tending to their off-duty hours.

Canadian-only leave clubs were established in London as early as August 1915, the first and most influential of which was the King George and Queen Mary Maple Leaf Club. It was developed by Lady Julia Drummond of Montreal as a place where the men "would have a warm welcome, congenial companionships and board and lodging at a reasonable rate; and where those who came from France could have a chance to get 'cleaned up' after the hardships of trench life." Famed author and poet Rudyard Kipling was an early supporter. The Club's first home was that of British socialite and philanthropist Ronald Grevile, located at 11 Charles St. in London.

It was, in principle, "solely, wholly, and only a Canadian Club, a Canadian Institution opened by Canadians, managed by Canadians and financed by Canadians" but maintained a strong British imperialist connection. The first Club building was open only to privates and non-commissioned officers and could accommodate up to 110 men. It boasted a billiards room, two dining facilities, a lounge, and a smoking room. British and Canadian newspapers were available in addition to writing materials, and imperialist art decorated the walls.

Cozzi describes the services offered by the Club: "Meal prices ranged from an affordable eight pence each for breakfast and lunch, while dinner, often consisting of soup, meat or fish course, vegetables, and dessert, cost a mere shilling. For breakfast soldiers would be treated to porridge, and either sausages, bacon, eggs or fish, bread and butter, and tea or coffee. For lunch, they could expect a meal consisting of cold meat or meat pies, potatoes, cheese, and dessert. A hot bath, pyjamas, and a bed for the night cost the soldier an additional shilling per night. Men could also have their laundry done and their kit cleaned and stowed away for safe-keeping. Organized around the needs of the men. breakfast was served as late as 1000 hours to allow tired soldiers the chance to sleep in. As well, soldiers leaving for the front were housed separately so that they would not disturb other men when they departed at 0400 hours to catch the early morning train back to their units. Soldiers could also rely on the club to keep them informed of military matters. The army, recognizing that a large number of Canadian troops frequented the institution, used the club's bulletin boards to post orders."

I hope you enjoyed this little glimpse into the soldiers' private time. If you did and are interested in reading more, the full article is available here: http://www.canadianmilitaryhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/5-Cozzi-Maple-Leaf-Club.pdf

Thanks for reading,

Delany (@DLeitchHistory on Twitter)

No comments:

Post a Comment