|

| The wall separating the Warsaw ghetto from the Aryan side of the city |

Almost two weeks ago, Dr. Grabowski presented us with an assignment which I found to be a profound experience in historical research, and I wanted to share it with readers as a sort of follow-up post to the one on Emmanuel Ringelblum. All document translations were done by Jan Grabowski, and I have obtained his permission for use of them as well as discussion of his assignment.

To begin, we were given three documents which were found in the archive that Emmanuel Ringelblum buried under the Warsaw ghetto, along with the translations into English. We then had to conduct research to identify all places and names found in the document, as well as outline the historical context in order to know as much about the circumstances as possible. The goal was to find as much information as we could so that Dr. Grabowski could determine our levels of research capability. (We weren't allowed to collaborate or share answers so he requested that I post this blog after the due date had passed).

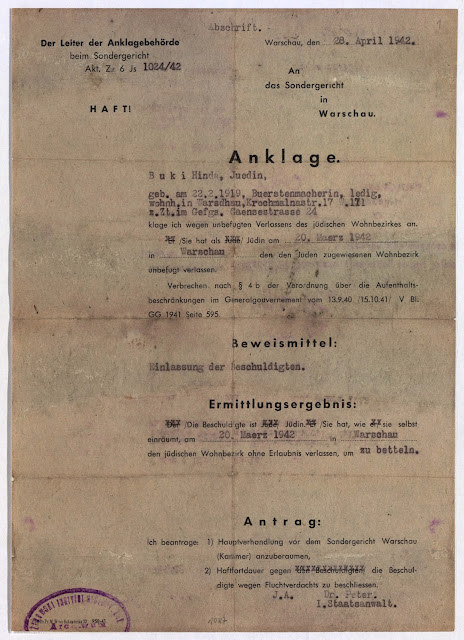

Here's the first document he gave us:

It says:

Warsaw,

28 April 1942

The Chief of the Prosecutor’s Office To the Special Court

of the Special Court In

Warsaw

Arrest!

INDICTMENT

Buki, Hinda, Jewess

born 22 February 1919, brush maker, single

resident in Warsaw, Krochmalna street 17 apt.

171

currently in prison, Gesia street 24.

Is accused of having left the Jewish Living

Area.

Being a

Jewess, she has left, on March 20, 1942, without authorization, the area

assigned to the Jews in Warsaw.

This is a violation of § 4 b of the Decree of

13 September 1940 and October 15, 1941 concerning the Limitations of Residence

for Jews in the General Government.

PROOFS:

The declaration of the accused

THE RESULT OF INVESTIGATION

The accused is a Jewess, she has admitted to

having left the Jewish Quarter in Warsaw without authorization, in order to go

begging.

REQUEST

I request: 1. To prepare proceedings in front

of the Special Court in Warsaw

2. To extend the period of arrest for the

accused who poses a flight risk.

Dr. Peter

Prosecutor.

Here is what I determined:

On 10 November 1941, Polish

police were ordered to execute women and children on the spot for trying to

leave the ghetto, and in late February of 1942 the German police began shooting

people attempting to cross to the Aryan side without warning. These changes are indicative of the diminishing role of the Special Court in

dealing with Jewish defendants. They also were put in place two months before Hinda Buki was arrested on 28

April 1942. On 29 May 1942, a conference of the Warsaw Special Court determined

that all prisoners incarcerated in the Gęsia Street prison were to be under the

Commissioner’s authority for evacuation to Treblinka, and it was requested that

the headquarters in Kraków no longer be informed of Jewish death sentences. The Jewish inmates of the Gęsia prison were among the first to be evacuated

during the beginning of the Aktion (liquidation

of the ghetto) on 22 July 1942.

Based on the information given in her indictment as well

as research conducted on her living conditions, it can be surmised that Hinda

Buki lived in a part of the Warsaw ghetto which was close to the homes and

activities of non-Jews, from whom desperation and starvation had forced her to

illegally beg. Upon being caught, she was immediately imprisoned according to

the first Special Court conference of 7 November 1941 which called for

interment of Jewish arrestees so as to eliminate their potential to escape and

avoid trial. Indeed, her form requests

an extension of the period of arrest “for the accused who poses a flight risk”.

The nature of the form itself is of note because of its structure as a sort of

checklist, where an administrator has clearly just filled in the information

specific to Hinda Buki as part of a numerous series of such papers.

To conclude, this document and case is unusual because it

was produced two months after German police had begun shooting without warning

Jews attempting to cross to the Aryan side, and six months after Polish police

were ordered to execute escaping women and children on the spot. Thus,

regardless of by whom she was apprehended, it is remarkable that Hinda Buki was

even sent to the prison in the first place. I believe that this document is

indicative of the amount of time it took to implement drastic and widespread

policy changes by the Special Court, as well as the discourse between those

administrative groups who wanted to continue legally persecuting the Jews and

those who wanted them dead faster and with greater efficiency.

Had she survived the conditions in the prison long enough

to be sent to Treblinka, she would have almost certainly met her death there.

The question remaining is not whether or not she was killed, but the manner in

which her death occurred.

Dr. Peter: He

is mentioned as having been one of several German High Court representatives at

a meeting with its Commissioner and deputy on 6 February 1942 which decided to

not file any new charges against Jews for offenses lesser than those which

carried the death penalty. Generally, officials of the Warsaw District’s political apparatus kept low

profiles and escaped punishment after the war, which, combined with the lack of

a given name, makes him difficult to locate. In the case of Dr. Peter, it may be of note that he fails to appear on a list

of Nazi jurists who remained active in Germany, which was compiled in 1968.

Hinda Buki: Her

name has not been entered into the Yad Vashem database of victims of the

Holocaust under any spelling or name order variants. However, there are a

number of results for the surname ‘Buki,’ with a large portion of those names

having originated in Lodz, Poland (possible relatives).The most definitive information regarding Hinda Buki comes from the Warsaw

Ghetto Database, which labels the information as being from the Ringelblum

archive. It mentions her arrest and imprisonment with the exact dates from the

indictment document, and describes her as starving in the Gęsia prison, swollen

with hunger and asking for help (translation from the original Polish).

Krochmalna Street: A lengthy, poor street before the establishment of the ghetto, it

became one of the most squalid in Warsaw during the occupation, with the corpses

of starved Jews littering the road. Roughly two residences away from Hinda Buki’s home (17 Krochmalna Street) was a

refugee centre at no. 21, where all four hundred residents died of typhus or

starvation. Given its major occurrence

of typhus, it was used by the Germans at the beginning of 1940 as a test area

for the planned formation of the ghetto due to a health authority report that

the street was the main source of epidemic in Warsaw (noted in Ringelblum’s

diary). However, the street was not entirely Jewish and not entirely incorporated into

the ghetto, as evidenced by the story of a young Jewish girl being smuggled out

of the ghetto to live with a Christian foster family at 33 Krochmalna until the

1943 uprising.

Gęsia Street Prison: In part supervised by the Jewish Ordnungsdienst, conditions there were worse than those present in

other Warsaw jails.The prison had opened during the summer of 1941 to remove a portion of the

Jewish inmates being held in “gentile” prisons, initially anticipating 500-600

but eventually serving a population of 1,500-1,800.

|

| The entrance to the prison |

“Regulation Concerning the Limitations of Residence

for Jews in the General Government": Issued

by Hans Frank on 15 October 1941, the decree introduced the death penalty for

all Jews intercepted outside the ghettos without an armband and proper

authorization, in addition to establishing the helping and sheltering of Jews

as a capital offense. It also strongly emphasized a previously-ignored request to stop releasing Jews

pending trial and deal with them more quickly, which created an unprecedented

level of legal and practical challenges.

Special Courts (Special Court in Warsaw) : Designed to incite fear and terror, these were established

in the German conquered territory as part of a two-tier system with the goal of

creating a legal frame for repression.The Special Courts heard cases involving crimes against wartime regulations,

and one was opened in Warsaw in early April 1940.

___________________________________________________________________________________

If you're still reading and made it all the way to the bottom of the page, you're one of very few people who know that Hinda Buki ever existed. Her story is just one of millions of terrible experiences, many of which we will never know, but I am grateful to have had the ability to understand what happened to her and share it with you.

Thanks for reading,

Delany Leitch (@DLeitchHistory)

Works Cited

Academia.edu. “List of Nazi

Jurists Active in Germany in 1968.” Accessed 2 February 2016.

GERMANY_IN_1968.

Grabowski, Jan. “Jewish

Defendants in German and Polish Courts in the Warsaw District,

1939-1942”. Yad

Vashem Studies 35 (2007): 49-80.

Grabowski, Jan (2016). German

Special Courts [Powerpoint Slides].

Jewish Historical Institute.

“A Story From an Old Photograph.” Accessed 29 January 2016.

Polish Center for

Holocaust Research. “Warsaw Ghetto Database.” Accessed 29 January 2016.

=zdarzenia.

Book

to Prague, Warsaw, Crakow & Budapest. Maryland: Jason Aronson Inc., 1999.

Yad Vashem The Holocaust

Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority. “The Central

Database of Shoah Victims’ Names.” Accessed 29 January

2016.

s_place=.

No comments:

Post a Comment